When multiple coating products come into contact, the results can range from flawless integration to catastrophic failure. Understanding coating compatibility isn't just about following manufacturer recommendations—it's about recognizing the chemical principles that determine whether different materials can coexist on the same surface. A single incompatible combination can lead to delamination, bubbling, discoloration, or complete coating failure, often long after the project seems complete.

Why Coating Compatibility Matters More Than You Think

The coatings industry offers thousands of products, each formulated with specific binders, solvents, and additives. When you apply one coating over another, you're essentially asking two complex chemical systems to work together. Some combinations create strong interlayer bonds, while others trigger adverse reactions that compromise both layers. The stakes are particularly high in industrial and commercial applications where coating failure can mean costly downtime, safety issues, or structural damage.

Many applicators assume that staying within a single product line guarantees compatibility, but even products from the same manufacturer can conflict if they're designed for different purposes or use incompatible chemistries. The key is understanding what makes coatings compatible—or incompatible—at a fundamental level.

Solvent-Based vs. Water-Based: The Primary Compatibility Challenge

The most common compatibility issue involves mixing solvent-based and water-based coatings. Solvent-based products use organic solvents as carriers, while water-based products rely on water. When you apply a solvent-based coating over a water-based product, the solvents can reactivate or soften the underlying layer, causing wrinkling, lifting, or poor adhesion. The reverse situation—water-based over solvent-based—generally works better, but timing is critical. The solvent-based coating must be fully cured, not just dry to the touch, or trapped solvents can interfere with the water-based topcoat.

The solution isn't to avoid mixing these systems entirely, but to understand when and how it's safe. Always allow solvent-based coatings to cure completely according to manufacturer specifications before overcoating with water-based products. When going the other direction, consider using a barrier coat or primer specifically designed to bridge the two systems.

Understanding Coating Chemistry: Epoxies, Urethanes, and Acrylics

Different coating families have distinct chemical structures that affect compatibility. Epoxy coatings, known for their durability and chemical resistance, can be overcoated with many products—but they're notorious for developing a waxy layer (amine blush) during cure that must be removed before topcoating. Urethane coatings offer excellent UV resistance and flexibility, but some formulations are sensitive to moisture during application and may not adhere well to certain primers.

Acrylic coatings are generally more forgiving and compatible with a wider range of products, which is why they're popular for both industrial and architectural applications. However, high-build acrylics may require specific primers when applied over previously coated surfaces. Oil-based coatings, while less common in modern applications, present unique challenges because they cure through oxidation rather than solvent evaporation, and this process can continue for weeks or even months.

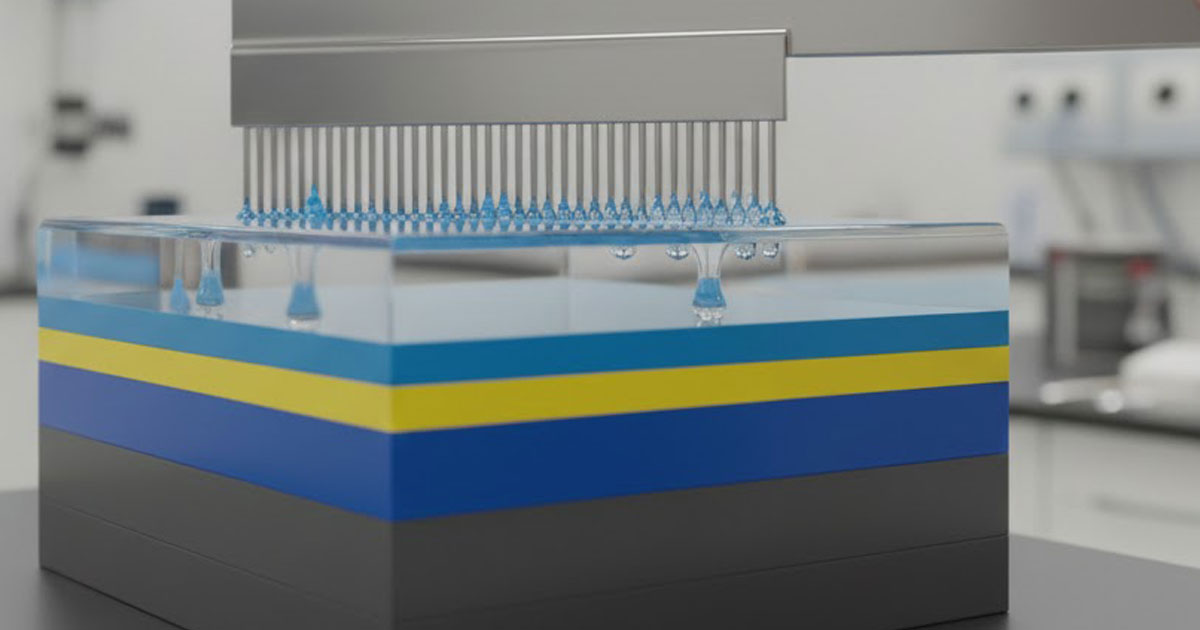

The Critical Importance of Recoat Windows

Most professional coating products specify a "recoat window"—a timeframe during which additional coats can be applied without special surface preparation. This window exists because coating surfaces undergo chemical and physical changes during cure. In the early stages, the surface is chemically active and forms strong bonds with subsequent layers. As curing progresses, the surface becomes increasingly inert, making mechanical adhesion (achieved through sanding or abrading) necessary.

Missing the recoat window doesn't make overcoating impossible, but it does require additional steps. You'll typically need to sand or abrade the surface to create a mechanical tooth that the new coating can grip. Some products specify whether light sanding or aggressive abrading is needed—follow these recommendations carefully, as insufficient preparation is a primary cause of delamination.

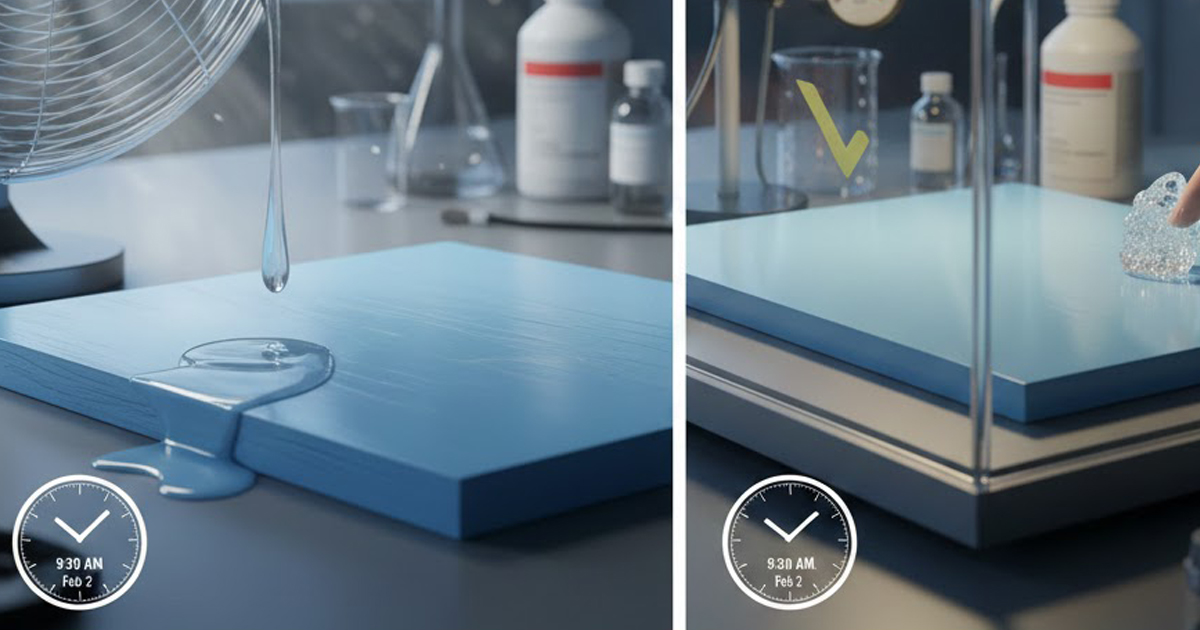

Testing Before Committing: Small-Scale Compatibility Checks

Before committing to full-scale application, always test coating compatibility on a small, inconspicuous area or test panel. Apply the complete coating system you intend to use, following proper cure times between coats. Look for signs of incompatibility like bubbling, wrinkling, poor adhesion, discoloration, or tackiness that persists beyond normal cure times.

For critical projects, consider performing adhesion tests using tape or cross-hatch methods after the test area has fully cured. This extra step can reveal weak interlayer bonds that aren't immediately visible. When working with unfamiliar product combinations, document your test results and cure times—this information becomes invaluable for future projects and can help identify issues before they affect large surface areas.

When to Use Barrier Coats and Tie Coats

Sometimes the best solution for compatibility challenges is introducing an intermediary layer. Barrier coats are designed to isolate incompatible coatings from each other, preventing adverse chemical reactions. Tie coats serve a similar purpose but focus specifically on improving adhesion between layers that would otherwise have poor bonding characteristics.

These products are particularly valuable when dealing with existing coatings of unknown composition or age. Rather than gambling on compatibility, a properly selected barrier or tie coat provides insurance against failure. However, these additional layers add cost, complexity, and time to your project, so they're best reserved for situations where compatibility is genuinely uncertain or known to be problematic.

Reading Technical Data Sheets for Compatibility Information

Manufacturers provide crucial compatibility information in their technical data sheets (TDS), but you need to know where to look and how to interpret it. The "overcoating" or "topcoating" section typically lists recommended products and application timeframes. Pay attention to substrate preparation requirements, which often include specific instructions for coating over previous applications.

Some TDS documents explicitly state which products should not be used together, while others provide more general guidance about coating families. When information is unclear or missing, contact the manufacturer's technical support team rather than assuming compatibility. A quick phone call can prevent expensive mistakes and project delays.

Temperature and Humidity: Hidden Compatibility Factors

Environmental conditions during application and cure can dramatically affect coating compatibility. High humidity can interfere with the cure of moisture-sensitive coatings like urethanes, potentially weakening interlayer bonds. Extreme temperatures—both hot and cold—can cause differential cure rates that affect how layers bond together.

These environmental factors are particularly important when using fast-cure products or working under tight deadlines. A coating that would normally be safe to overcoat after four hours might need eight hours in cold conditions, or just two hours in hot weather. Always adjust recoat times based on actual conditions, not just what's printed in the TDS.

The Bottom Line: Compatibility Is About Prevention

Coating compatibility problems are far easier to prevent than fix. Once incompatible coatings begin reacting, your options are limited—usually to complete removal and reapplication. By understanding the chemical principles behind compatibility, respecting recoat windows, testing uncertain combinations, and following manufacturer guidelines, you can avoid the vast majority of compatibility issues. When in doubt, the conservative approach—additional testing, barrier coats, extended cure times—is always worth the extra effort compared to dealing with a failed coating system.